French railway major Alstom, which has completed building the first of 800 planned Electric Locomotives in a joint venture with the Indian Railways in Madhepura, is looking at making India a supply base for its global market. Chairman Henri Poupart-Lafarge told in an interview that Alstom’s proposed merger with Siemens Mobility will bring more investments and solutions to India, its fastest-growing market outside France. Edited excerpts:

Do you spot some changes in India?

The first time I visited was in 2000 and I have been here many times since then. There has been a tremendous change in terms of size and scale of what we do in India. What we do in transportation has been multiplied by 10. Speed of implementation has improved.

How has the investment climate in India changed over the past few years?

In the past few years, we have invested tremendously in India. I think we have grown and multiplied investments by a factor of three to four. In terms of people, we have 3,600 where a couple of years ago, we were a couple of hundred. So it shows the momentum of India and the business friendliness in India is increasing. It is important not only for the Indian market because it is booming in this sector, but also as a global platform and we are exporting from India to places like Australia, Europe.

Do you plan to make India a leading supply base for your global market?

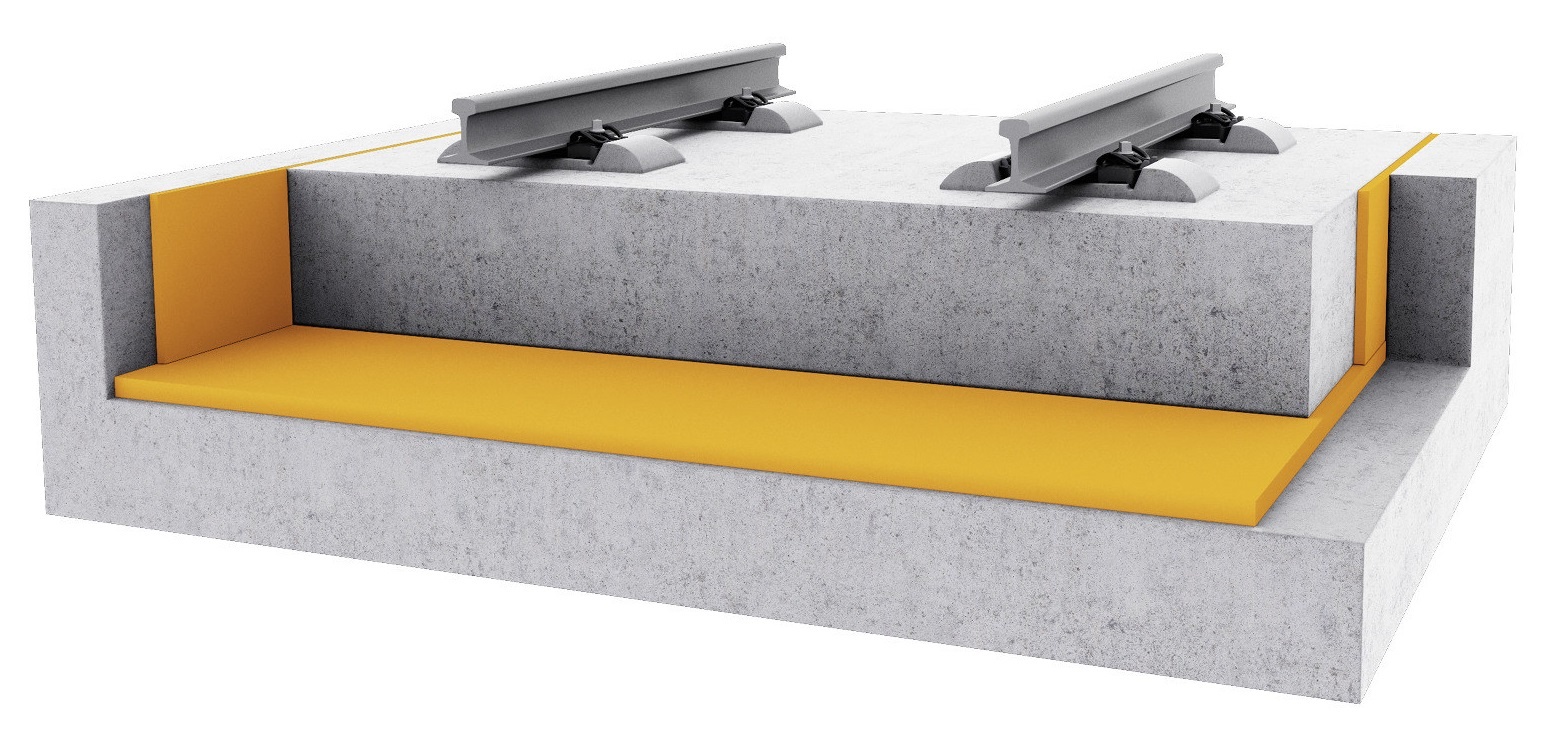

We had standard product ranges in India in the past, then we diversified into signalling, which is very important for India. The factory at Madhepura is the entry into mainline – the locomotive world. We are also now increasingly entering into infrastructure activities and we are implementing a project in the dedicated freight corridor, but all this infrastructure is helping meet the needs of the Middle East. So India is growing a full range of activities – from mainland to urban, infrastructure, services as well. So this is for the Indian market and worldwide.

What is driving so much activity from Alstom in India?

In our world of public transportation, urban transportation, we need to be very close to all our customers, to be locally based to better serve our customers. This is definitely the case in India. At the same time, we need to be competitive. So the huge Indian platform is also a strong enabler for global competitiveness and it’s not only a question of cost but also of innovation. The urban transportation will require more and more digital technology in order to reach a greater level of efficiency.

What are your plans for Madhepura factory?

We have achieved this with some scepticism, to begin with. Now we need to go from producing a fantastic product to addressing the pollution problem. That will require heavy investment in Madhepura, but also, as importantly, a lot of investment in the supply chain. We want to develop a smooth supply chain in order to produce the remaining 799.

Can you put a timeline to it?

At full speed, we will deliver 100 per year, so on the whole it’s a 10-year contract and then, of course, we have the full maintenance. Of course, we see it as a main challenge but we see also this factory as a beginning of an extremely long history. The need for locomotives is huge in India.

As part of global restructuring – Alstom’s merger with Siemens – how does it change the India strategy given the financial stronghold of the merged entity?

The merger itself is here to speed up our strategy. So basically, the merger will allow us to be even closer to our customers and you can see this example in India where Siemens is also strong in terms of rail electrification. We need to think about our positioning and what we can bring to our customers in terms of global solutions, financing. We want to be the technological provider and the partner not only to the operator but to the railway authorities.

So does it translate into more investments along with new business models in India?

Absolutely! In terms of being the origin of engineering, everything will mechanically double in size, in terms of exports from India, in terms of engineering forces, etc. In addition, because of the changed business models, we need to invest more in India in terms of global solutions.

Indian Railways is investing a lot of money in upgrading its infrastructure and modernising it. What do you see as the major roadblocks?

We have this huge modernisation challenge and environmental challenge but in addition to that, you also have the safety challenge which comes into play. Environmental challenge is basically the electrification and its huge work to be done.

There is safety challenge, which requires huge level of investment in terms of signalling. Indian Railways is planning a signalling contract. What kind of business does it mean for Alstom?

Europe has been probably one of the pioneers of technology for signalling and similar to Europe, India has a high-density network, so I think there are some discussions around bringing the European technology to India and, of course, we will be more than happy to bring that. There are two elements – the pure technology, which is extremely important in the Indian context, but also it is an extremely ambitious project of management challenge because you need to install on mainline – it’s a little bit more complex.

Are you looking at more JVs in India?

We are discussing setting up joint ventures with some of our suppliers in order to balance the approach. Today, we cannot name the players. We are encouraging international players like ABB to localise in India the products we need for supporting our project in Madhepura. This also indirectly brings a lot of investments, skills to the country.

But there are railway projects going on for 40 years. Has execution actually changed?

Delhi Metro started more than 15 years ago and it has grown. The momentum has changed from one city to a large number of cities. For Indian Railways, in two years, we have developed locomotives in Madhepura, set up a new factory and manufactured. The speed of implementation has been fantastic. We built it in joint venture with Indian Railways and they did everything from certification onwards.

What are the focus areas for you?

Our focus is to add new technologies, and engineering capabilities in India. In the last 10 years, we have reached a stage where everything that’s needed is done in India — we have a factory in Coimbatore, for metros in Chennai and now one for locomotives in Madhepura. We will add manufacturing capabilities. Engineering is growing 20-25% every year. Now, we have 1,500 engineers in Bangalore, which is more than 20% of all engineers in Alstom. Manufacturing capability for India and global operations is 50:50. On engineering, it is 80:20.

Any other areas that you are interested in?

Electrification, of course. It is the future — whether you talk about electrification using catenaries, or the introduction of hydrogen trains, which is a terrific product to get rid of diesel. It has been worked out in Germany and a lot of countries have tested it out, including Canada. The cost of this train is similar to a cost of a normal train. But then, there is a cost of infrastructure which is difficult to estimate. We need to have hydrogen tanks on the poles, etc. It is a very good combination with renewable energy. Because when you have excess power, you transform that into hydrogen.

Talking about high-speed trains. India went with Japan partly because of the funding. How do you compete with these kinds of models?

We are totally dedicated to the ‘Make in India’ policy. We want to leverage that, localise and probably get some local financing. Of course, if you have external financing tied to loans, then, they will not comply with a ‘Make in India policy’. That’s another way of doing business but we are not there.

How do you compete when technologies are pushed based on funding?

In the case of Japan, you have seen that in some situations an input from Japan can at the end of the day, cost more to the Indian authority than making locally with local financing. What is being bought through Japanese financing from Japan might at the end of the day be more expensive than products being made by Japan in India.